Since the emergence of the concept of sustainability in the 1990s, governments and individuals have been multiplying efforts at all scales to initiate a transition towards sustainable diets, favoring seasonal agro-ecological production and fair and local production-consumption networks [1].

According to the EAT-Lancet Commission (2019), when it comes to protecting the environment, food remains one of the biggest levers and means of action to reduce your carbon footprint [2]. There is nowadays a recognition that the current global food system is indeed unsustainable, responsible for 30% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 70% of water use and a huge loss of biodiversity [2]. And 49% of the habitable land is used by agriculture [3].

By switching to a more sustainable diet, we hold a possible solution to improve not only our own health but also that of the planet. It is not the food itself that is sustainable but the diet as a whole that can be sustainable and healthy.

Food choices for a sustainable diet

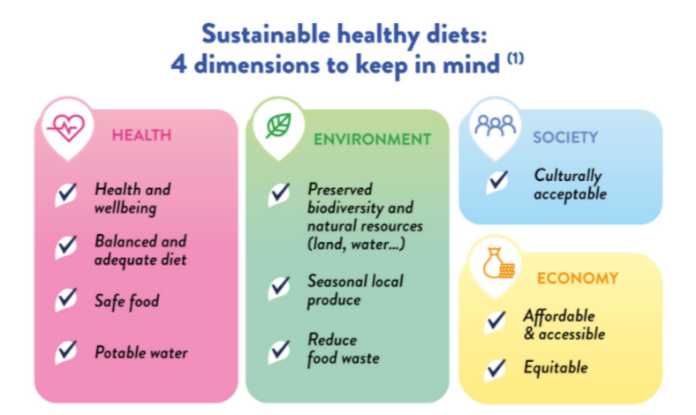

A healthy and sustainable diet is defined by four dimensions [4]:

- with safe nutritionally-dense foods, included in a balanced healthy diet

- culturally acceptable

- accessible, affordable and equitable

The production must have a low impact on environment and preserve biodiversity and natural resources, ideally produced and consumed locally [1].

The best balance between these aspects is achieved by choosing a varied predominantly plant-based diet, combined with a reduction of food waste. Elements that are being part of the diet should be sourced in sustainable food production systems, i.e., local and seasonal [5].

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) ‘Sustainable diets are those diets with low environmental impacts which contribute to food and nutrition security and to healthy life for present and future generations. Sustainable diets are protective and respectful of biodiversity and ecosystems, culturally acceptable, accessible, economically fair and affordable; nutritionally adequate, safe and healthy; while optimizing natural and human resources.’ [1]

A recent publication [5] examines the benefits and limitations of different types of diets in terms of health and nutrition, affordability and accessibility, cultural (ethical and religious) acceptability, and the environment. This review suggests that flexitarian diets and territorial diets (TDD) (Mediterranean or New Nordic diets for instance) can meet the energy and nutrition needs of different populations without the need for dietary education or supplementation.

NB : Flexitarianism combine large amounts of plant-sourced foods, low levels of meat but moderate volume of poultry, fish, eggs and dairy, while TDDs are region-specific flexitarian diet that primarily includes seasonal, locally-sourced foods.

Moreover, even if further studies are required to define more precisely optimal sustainable healthy diets (taking into account the 4 pillars underlying these diets), those diets may have a more sustainable impact on the environment than Western diets (especially if diets include locally sourced seasonal foods). They may be more acceptable and easier to maintain than less diverse vegan/vegetarian/pescatarian diets for people transitioning from Western diets to sustainable healthy alternatives.

Nutrient-dense and healthy

A sustainable food is nutritionally safe, dense and healthy, it must prove a good nutrient-density, including a high-quality protein content, as well as fibers and vitamins.

Nutrition density refers to the “concentration of nutrients per amount food or caloric contribution of that food” [6]. It is the amount of nutrients provided by a portion of food, knowing its caloric intake. A nutritionally dense food provides many more nutrients than calories relative to the body’s needs.

The choice of sustainable foods within a varied healthy diet, such as flexitarian diets or TDDs, improves global health by reducing malnutrition and NCDs risk (no-communicable diseases) and nutritive deficiencies, but also by meeting the energy and nutrition needs without the need for dietary education or supplementation [4,5].

Contribute to protect biodiversity, while preserving natural resources

By adopting new food consumption habits on a collective and individual scale, it is now possible to reduce food-related GHG emissions and protect the planet’s natural resources.

Moreover, supporting a healthy and sustainable dietary pattern is one essential way to limit and prevent environmental degradation caused by what ends up on the plate [4]. Indeed, our global food system is today unsustainable because largely based on intensive exporting agriculture, and dependent on phytosanitary products and agricultural fertilizers [4]. The use of such chemicals and deforestation are a main driver of biodiversity loss, both in soil and aquatic ecosystems [4].

“Achieving healthy diets from sustainable food systems for everyone will require substantial shifts towards healthy dietary patterns, large reductions in food losses and waste, and major improvements in food production practices.” – Willett W et al, 2019

Economically accessible and culturally acceptable

Sustainable food comes from responsible supply chains, valuing short circuits and local seasonal production.

Reducing the transport of goods and food is a major step in handling climate change already in place [5,8]. Buying over short distances limits the energy consumption of transport and the chances are local foods will also cost you less.

Furthermore, direct and seasonal sales from farmers to consumers through new local organizations is the best way to get good prices in a fair trade and educational relationship that reconciles urban citizens and producers [1,8].

Regarding sociocultural aspects, sustainable healthy diets are built considering with the respect of local culture and traditions. Culinary tools, practices and values, even religious and ethical believes regarding the way the food is produced, prepared and cooked, should be taken into account [4,5]. Furthermore, sustainable diets adoption must cut down gender-related impacts, especially with regard to time allocation (e.g. buying and cooking, water and fuel purchase) [4].

4 resolutions for a more sustainable diet

Our food choices may affect the future: thus, by reducing wastage and making healthier food choices, we can cut global GHG emissions by up to 50% [12,13]. In daily life, we can follow these resolutions :

- Reduce the domestic food waste. With a better understanding of use-by dates, a weekly planned menu and proper storage conditions, we can make sure that all the products we buy will be consumed (and our wallet will also thank us).

- Prefer seasonal and locally produced food [4,5]. Locally produced and seasonal fruits and vegetables are often low calories foods, rich in vitamins (A, C and K), minerals (copper, manganese and magnesium) and fibers [9,10]. It is necessary to keep in mind that the GHG Emissions reductions achieved by substituting plant-based foods for animal foods are offset by the environmental impacts of transporting out-of-season fruits and vegetables around the world, especially by plane [5]. Hence the importance of respecting the seasonality of products and ensuring that they are sourced locally as much as possible.

- Limit the intake of added-sugar and ultra-processed foods (so-called “empty calories”). The latter encompass foods containing very low levels of essential nutrients (proteins, vitamins and minerals), in favor of fats and sugars that create an energy excess.

- Add more nuts, seeds, beans, legumes and sprout in the diet. Nuts and seeds stand out for their protein, vitamin E and polyunsaturated fat content. The texture and shape make them the food of choice for balanced, nutritionally rich snacks [9]. In terms of global health and reduction of non-communicable diseases burden, the FAO emphasizes the importance of increasing nuts and seeds consumption [4]. However, although they show several nutritional benefits and a low energy use, the latter are deemed the fourth most water-irrigated foods as they are grown in dry climate regions, mostly in USA [11]. Consequently, their consumption must be reasonable. Beans, legumes and sprouts are plant-based protein sources and support the soil enrichment in nitrogen for the recovery of land they are grown in. [9]

Can yogurt be part of a sustainable diet?

Daily consumption of yogurt is an effective way of meeting nutritional requirements while combining a balanced calorie intake [14,15]. Yogurt brings through a low calory density formula numerous positive nutrients like protein, calcium, zinc, potassium, as well as vitamins (Vit. B) and probiotics for gut health [15,16,17]

Yogurt is a dairy product. Unlike livestock and especially beef, which is considered the biggest contributor to GHG emissions [4,18], dairy has a smaller carbon footprint. According to the FAO, the global dairy sector contributes to 4% of the global GHG emissions [20]. Even within dairy categories, yogurt and milk have lower carbon footprint than cheese [19].

According to the FAO/WHO guidelines on sustainable and healthy diets, a moderate dairy intake that respects nutritional recommendations fits into sustainable and healthy diets [4,19].

Yogurt is indeed a nutritive product with a moderate effect on the environment. Moreover, within a balanced diet, yogurt is one of the most common and accessible products. It can be easily found in small, medium and large stores, and fermented dairy products, as well as yogurt, are already part of several traditional diets around the world : greek yogurt, kefir, skyr, labneh and many more. Eventually, it stands amongst of the lowest cost sources of calcium and a very affordable high quality protein source [20].

References:

-

Burlingame B, Dernini S. Sustainable diets and biodiversity: Directions and solutions for policy, research and action. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2010.

-

Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):447-492.

-

Ritchie H, Roser M. 2019. Land Use. Our World Data.

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. (2019) Sustainable Healthy Diets, Guiding Principles.

-

Luis A Moreno, Rosan Meyer, Sharon M Donovan, Olivier Goulet, Jess Haines, Frans J Kok, Pieter van’t Veer, Perspective: Striking a Balance between Planetary and Human Health—Is There a Path Forward?, Advances in Nutrition, 2021; nmab139

-

Drewnowski A. et al., Nutrient profiling of foods: creating a nutrient-rich food index, Nutrition Reviews, 2008, 66 (1): 23-39

-

WWF France. Towards a low carbon, healthy and affordable diet. 2018

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sustainable Food and Agriculture. [Online].

-

WWF, Future 50 foods. February 2019.

-

Randhawa M et al. (2015) Chapter 18: Green Leafy Vegetables: A Health-Promoting Source. In: Watson RR (ed) Handbook of Fertility. Academic Press.

-

Tom, M.S., Fischbeck, P.S. & Hendrickson, C.T. Energy use, blue water footprint, and greenhouse gas emissions for current food consumption patterns and dietary recommendations in the US. Environ Syst Decis, 2016, 36:92–103

-

Hallström E, Carlsson-Kanyama A, Börjesson P. Environmental impact of dietary change: a systematic review. J Clean Prod. 2015; 91:1-11.

-

Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJM, et al. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165797.

-

Keast DR, et al. Associations between yogurt, dairy, calcium, and vitamin D intake and obesity among U.S. children aged 8-18 years: NHANES, 2005-2008. Nutrients. 2015;7(3):1577-93.

-

Hess J, Rao G, Slavin J. The Nutrient Density of Snacks: A Comparison of Nutrient Profiles of Popular Snack Foods Using the Nutrient-Rich Foods Index. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017 Mar 30;4:2333794X17698525.

-

Rolls B., The Ultimate Volumetrics Diet, William Morrow, 2012.

-

Smethers A. & Rolls B., Dietary management of obesity: cornerstones of healthy eating patterns, Med Clin N Am, 2018, 102 : 107-124

-

van Hooijdonk T, Hettinga K, Dairy in a sustainable diet: a question of balance, Nutrition Reviews, 2015; 73 (1): 48–54

-

Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Martin A, et al. Energy and nutrient density of foods in relation to their carbon footprint. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:184–91.

-

FAO, 2010, Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Dairy. Sector : A life Cycle Assessment, p.13.

For more information:

- Short video: How can our diets protect both, human and planet health?

- Go local for a healthy sustainable diet

- Q&A about sustainable diets: What would a more sustainable diet mean for you?

- Q&A about sustainable diets: What is a flexitarian diet or flexitarism?

- Conference by Franz Kok – ASN, Baltimore, 2019 – Dairy & yogurt as part of sustainable diets

- Conference by Adam Drewnowski – ICD Granada, 2016 (Can yogurt be part of a sustainable healthy diet?)